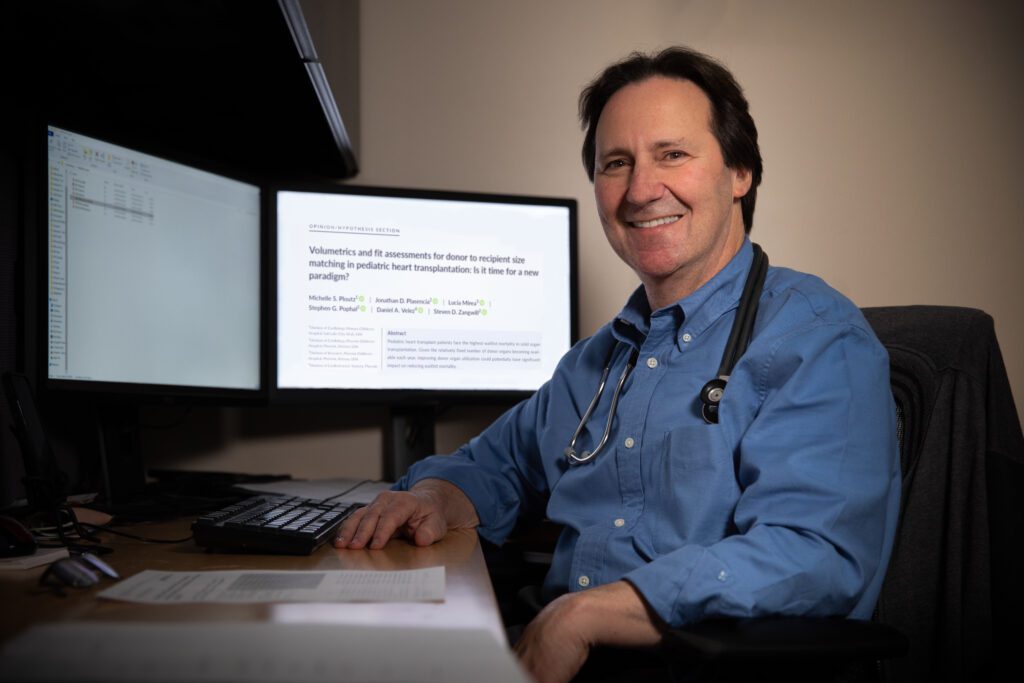

As a boy, Dr. Steven Zangwill was highly curious. Whenever he encountered a medical problem, such as asthma or a broken bone, he wanted to know how it all worked.

It’s a trait that he’s carried into adulthood and his career as a pediatric cardiologist. When an obstacle surfaces, Dr. Zangwill spares no effort. He snaps photographs. He draws graphs and charts of the tiniest components. It doesn’t matter if the issue is a faulty house fixture or a disease in the body of a child—Dr. Zangwill approaches it all with precision.

Finding flaws in the field

When it comes to heart transplantation, there are problems that Dr. Zangwill isn't willing to accept. For starters, usable organs are often discarded.

Pediatric heart transplant patients have the highest solid-organ waitlist mortality rate in the U.S. at 17 percent. Despite this, approximately 20 percent of pediatric donor hearts appropriate for transplant go unused.

Doctors check a long list of metrics before accepting an organ. “If one center turns it down for one reason, and another says no due to a different factor, eventually a good heart gets rejected because of distance,” Dr. Zangwill explains. “Once you get 1,500 miles away, the relative risk increases and the organ is less likely to be accepted.”

The size of the heart is one critical metric on the list. The current method of determining if a donor heart is the right size for a patient is to compare the body weight of the donor to the recipient. “It doesn’t make sense,” Dr. Zangwill says. “The size of the heart is not in direct relationship to the weight of the individual, particularly for the children we are transplanting.”

He argues that weight-based size matching, in which body weight is used as a surrogate for heart volume, has inherent problems. Children with heart complications typically have enlarged hearts, independent of their weight. Weight-based practice also assumes the donor heart is of normal size; however, the relationship between weight and heart size may vary even in this population.

Regardless of these inaccuracies, weight-based size matching remains the dominant way.

Going against the grain

Over the past decade, Dr. Zangwill has invested countless hours on an alternative method: volume-based size matching. In the beginning, he used echocardiograms (ultrasounds of the heart) and mathematical equations to estimate total cardiac volumes. This change generated promising results—Dr. Zangwill noticed he was finding heart matches for his patients faster.

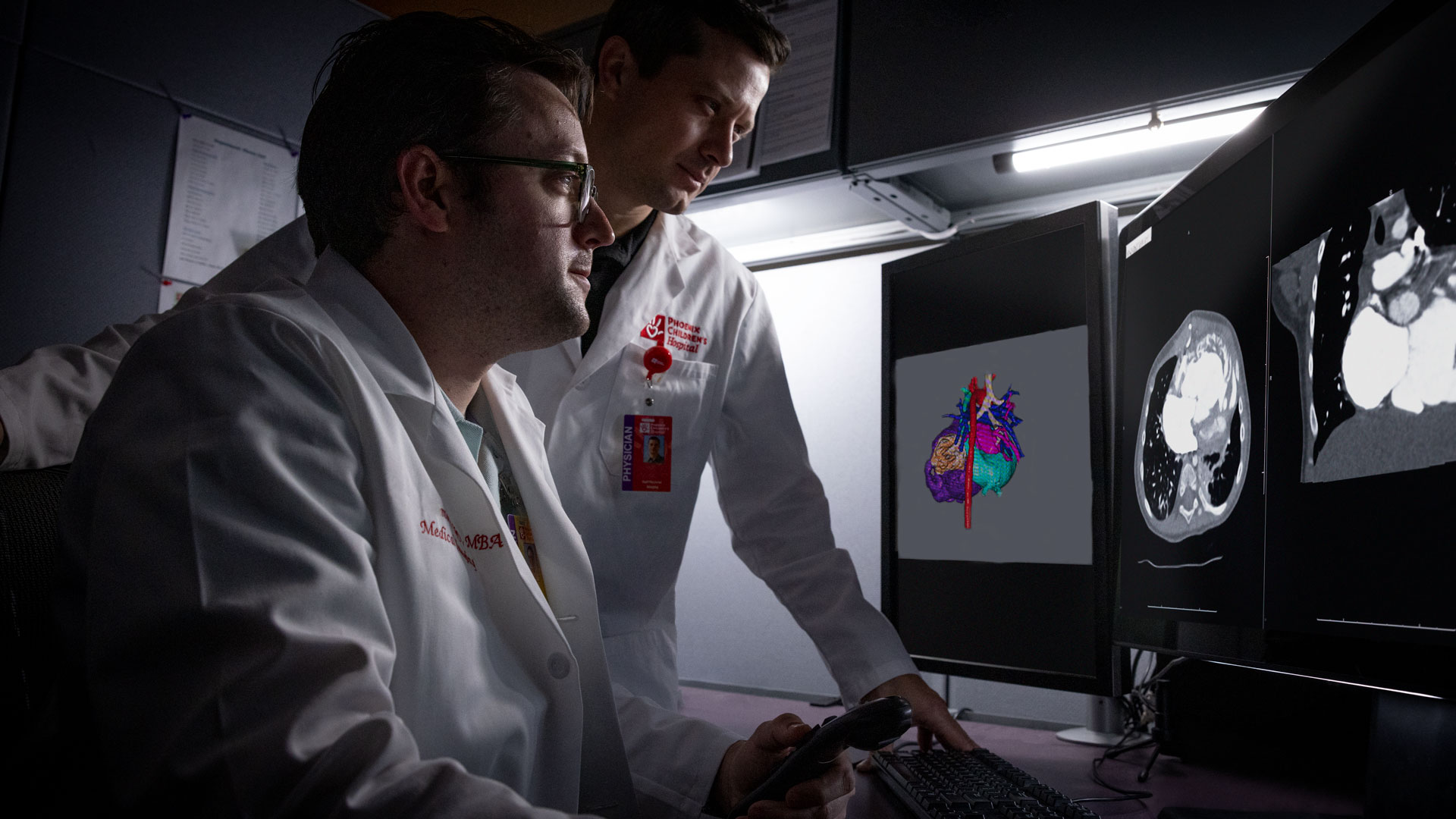

When Dr. Zangwill moved to Phoenix in 2015, collaboration took his idea to the next level. Phoenix Children’s robust research infrastructure connected him to individuals with complementary skill sets.

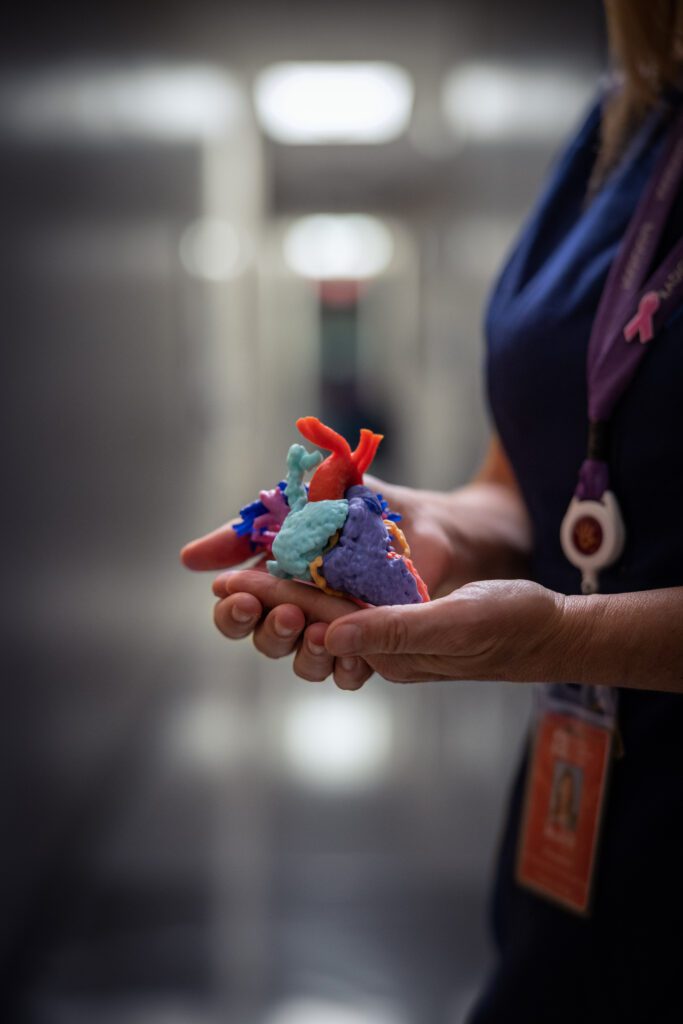

He partnered with Jonathan Plasencia, a biomedical engineer on the research team, to improve the feasibility of volume-based size matching. The team measured the total cardiac volumes of 100 healthy children using MRI and CT scan data. They then developed a “healthy heart library,” with virtual 3D reconstructions of the healthy hearts catalogued by size. This allowed doctors at Phoenix Children’s to use volume-based decision making to evaluate potential donors.

Selecting with confidence

With the ability to use volume-based size matching, Dr. Zangwill began to accept hearts that other hospitals might not have considered. His bold approach is evident in the story of two Phoenix Children’s patients—a pair of sisters who needed heart transplants.

The elder had cardiomyopathy, a disease of the heart muscle that makes it difficult for the heart to pump blood. “She had a rough course while waiting for transplantation,” Dr. Zangwill recalls. “We got an offer beyond most doctors’ acceptable weight range. We estimated the volumes and determined the heart was the right size. We took it.”

The donor was more than three times the weight of the girl. Many heart centers, depending on their recipient, are willing to take a heart from a donor no more than twice the weight of the patient.

A year later, the younger sister experienced similar challenges. She was on a ventilator and in dire need of a heart transplant. To Dr. Zangwill’s surprise, a heart was available from a donor at the same weight ratio as the elder sister’s case. He welcomed the offer.

- “I get excited because almost nobody else in the country would have seen those [donor heart] offers.”Dr. Steven ZangwillDirector of the Heart Transplant and Heart Failure Programs at Phoenix Children's

The girls are now several years post-transplant. “They’re thriving,” Dr. Zangwill says. “I get excited because almost nobody else in the country would have seen those offers.” Many heart centers list conservatively by weight, which restricts the donor pool, and thus a patient’s options. A smaller donor pool leads to organ waste because physicians are less likely to find a nearby match.

Over a 15-year-period, doctors nationwide have transplanted only 30 hearts with donor-recipient weight ratios greater than three. Phoenix Children’s is elevating the standard—their transplant team has completed four since 2015.

Spreading the word

Thanks to the pioneering efforts of Dr. Zangwill and his team, Phoenix Children’s Center for Heart Care has transitioned towards volume-based size matching. The shift is spreading; a few known centers have adopted the method nationally, and Dr. Zangwill is on a mission to make this metric more widely accepted.

Dr. Zangwill has always been drawn to high-risk care. But the adrenaline is not the only reason. He finds the most gratification in his interactions with families. “The relationship you develop when you’ve been through the worst with them is different. But when everything goes as planned, I get to ask a child how many goals they scored in their soccer game. Then, I sometimes get to follow them for decades afterwards. I wouldn’t trade what I do,” Dr. Zangwill says.

Consider supporting the cutting-edge research and care of Phoenix Children’s Center for Heart Care.