When Megan was pregnant with her daughter, Cloey, in 2000, she had no reason to expect anything out of the ordinary. But that all changed shortly after Cloey’s birth, when Cloey was diagnosed with a rare genetic disorder that gives rise to many conditions such as Down syndrome, cerebral palsy and vision loss. Hospital stays and visits became a constant and draining part of Cloey’s childhood. But, when Cloey turned 9, the development of a brand-new medical program at Phoenix Children’s would radically change things for the better.

At the time, Tressia Shaw, MD, worked as a primary complex care physician at Phoenix Children’s. “It surprised me that we didn’t have a palliative care resource, especially since we were a large hospital serving children with complex medical conditions,” says Dr. Shaw.

Palliative care aims to optimize quality of life for children with life-limiting or life-threatening diagnoses. For children with complex needs, palliative care has been shown to reduce hospital stays and emergency department visits. This medical specialty is new and growing—it became nationally approved in 2008. Dr. Shaw spearheaded the launch of Phoenix Children’s palliative care program the following year.

- “They open the picture up, they make sure we know what we are saying ‘yes’ and ‘no’ to.”MeganCloey and Rockwell's mom

“We have wonderful specialists here focusing on their own specializations—the GI doctor is looking at the digestive system, the neurologist is looking at the brain. In palliative care, we bring the subspecialities together in a big-picture way to help families navigate what’s coming next. Without our program, a child’s unique trajectory and goals may not have the same continuity,” Dr. Shaw says.

Dr. Shaw and her team often spend up to two hours talking with patient families, seeking to help each family define what optimal quality of life looks like for their child. “They open the picture up, they make sure we know what we are saying ‘yes’ and ‘no’ to,” Megan says. Conversations like these proved to be significant for Megan and her husband, Ty.

The value of a medical quarterback

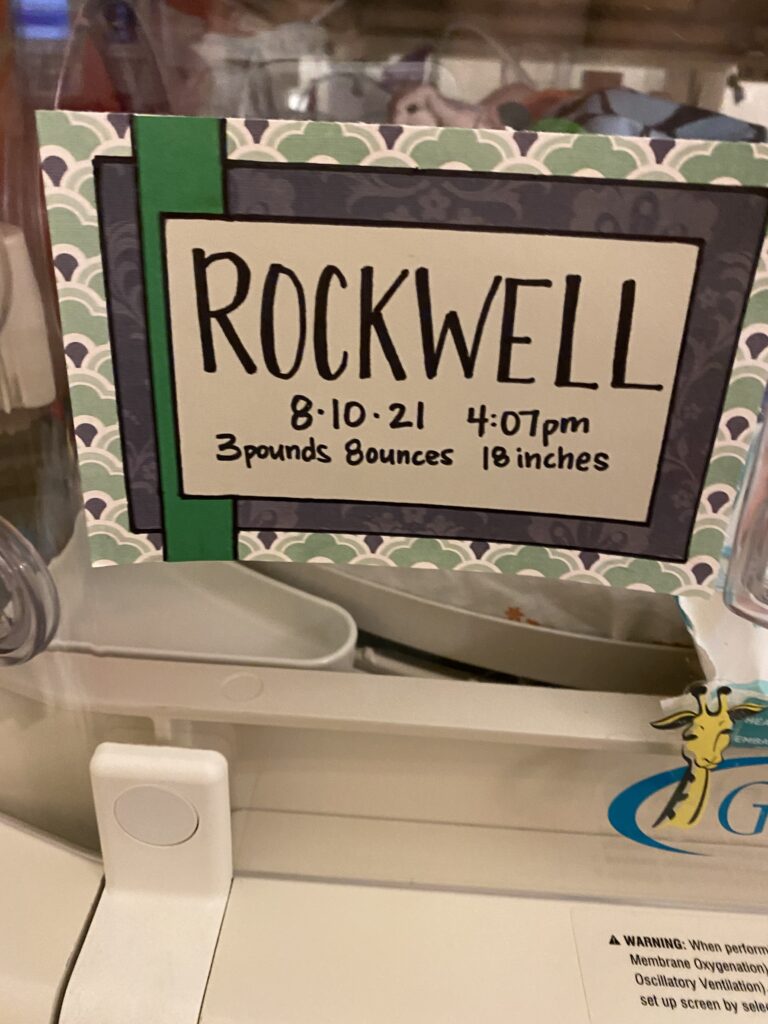

After Cloey, Megan believed she would never bring another child into the world with the same condition, as it increases the likelihood of a miscarriage or stillbirth. In 2021, she discovered she was pregnant with a boy, whom they named Rockwell. A prenatal genetic test revealed he had the same genetic condition as Cloey. But this time, Megan and Ty were prepared from the beginning, thanks to the palliative care program.

JonMark Moorington, MD, served as Rockwell’s palliative care physician during Megan’s pregnancy. The relationship Rockwell’s parents built with Dr. Moorington helped them establish what they wanted to do if a crisis occurred at birth. Morrington’s role was like that of a football team’s quarterback—he met with Megan and Ty to create a medical care playbook, which he then relayed to a team of interdisciplinary specialists.

- “It was a huge relief to have a quality-of-life conversation with someone who understood Rockwell’s life was valuable.”MeganCloey and Rockwell's mom

“It was a huge relief to have a quality-of-life conversation with someone who understood Rockwell’s life was valuable,” Megan expresses through tears. “We knew we wanted our baby, but we did not want him to suffer. If he only had a few hours to live, we decided we weren't going to put tubes down his throat. Instead, we would hold him and be left alone.”

According to Dr. Shaw, crisis is the worst time to make decisions because control is lost. If life expectancy is potentially short for a child, her team tries to give the parents as much control as possible by creating a plan beforehand. “We can make ‘What if …’ plans and then put them away in a box. Maybe we never have to use them,” Shaw explains.

When Rockwell was born, Megan held him for a second before handing him to the neonatologist. He weighed 3.5 pounds, and his tiny features displayed characteristics of Down syndrome. The neonatologist then checked his vitals. “I remember him saying, ‘Megan, he’s okay, do you want him back?’”

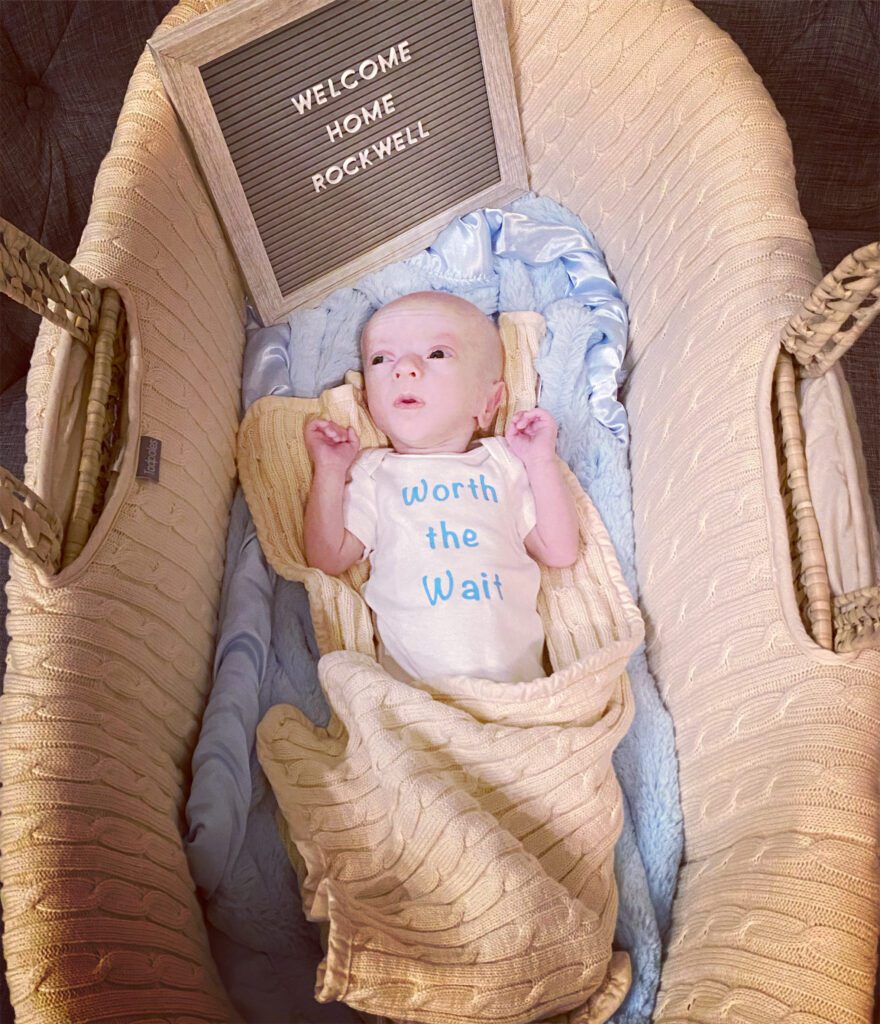

Normally, there would be a rush to transfer babies like Rockwell to the NICU. But since the family had plans in place, Rockwell was given back to Megan, and she held him for a long time. “That was one of my favorite memories,” Megan adds.

Setting a baseline

A family’s relationship with palliative care doesn’t end at birth—the team remains involved in the care of a child with lifelong challenges. One way they do this is by understanding the child’s baseline by asking questions such as: “What is your child like at home? What does a good or bad day look like? What brings your child joy?” The family’s input influences future treatments.

In Cloey’s early years, questions like these often weren’t asked due to the absence of palliative care. “Quality of life for kids wasn’t talked about,” says Megan. “Things weren’t coldhearted back then; doctors just didn’t have the training until palliative care was formed. The specialists that worked with my daughter years ago have a better understanding now.”

In Rockwell’s case, he’s happiest when he’s at home with family. He’ll spend hours playing in the blinds, delighting in the sun’s reflective rays. Sunlight is one of the few elements he can see. Vision and hearing loss, decreased muscle tone, and difficulty swallowing are symptoms Rockwell experiences. His medical needs require many appointments in neurology, endocrinology, audiology, orthopedics and gastroenterology. Palliative care coordinates his appointments, thus reducing the time he spends at the hospital.

“He’s happy, and I don’t think he is in pain,” Megan says. “We no longer have endless hospital stays and blood draws like we did with my daughter. Thanks to coordination of care, Rockwell spends more time at home, which helps a lot.”

The power of generosity

Nationally, palliative care programs receive about one-third to one-half of their funding from philanthropy. At Phoenix Children’s, palliative care donations fully support bereavement services and some of the team members’ salaries. “We are a tight team of physicians, social workers, Child Life specialists, psychologists and bereavement coordinators. It is imperative that these people are involved in caring for the children we work with,” says Dr. Shaw.

Quality of life looks different for every family. Sometimes it is about helping a child feel comfortable while sleeping or eating. For others, good days stem from bigger adventures, such as soccer games or trips to the beach. No matter the family’s wishes, the palliative care team maintains the same overarching goal: design a custom care program that makes the most out of every day for each child.

Since 2009, Phoenix Children’s Palliative Care program has provided specialized medical care for nearly 6,000 children with complex conditions. When children like Rockwell and Cloey have access to palliative services, their quality of life is protected.